Carnival

The festivities of Roman carnival concentrated on the week before Lent and were strictly regulated. Carnival had, with its own celebrations and rites an inverted and liberating function, both at an individual and collective level. Every year the warnings and prohibitions of the authorities tried to control and circumscribe the transgressions of carnival.

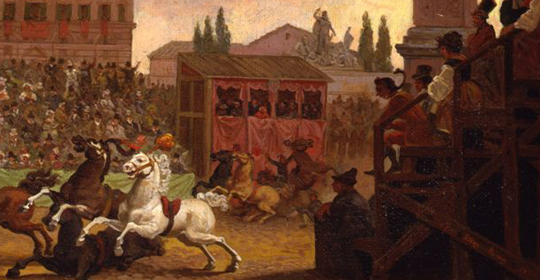

The display of masks (images of the other), the jokes, the confetti wars, the processions of allegorical floats, the horse races, the “moccoletti” (where everyone tried to put out the candles everyone else was holding), took place primarily in the Via del Corso and in the nearby streets, where in 1466 Pope Paul II had transferred the carnival from Piazza Navona and Testaccio, which up until then had been the places set aside for public carnival celebrations.

A central and recurrent element of the carnival is represented in the “barberi” race. The “barberi”, small, robust horses from North Africa, raced the length of the Via del Corso, without jockeys, and between two rows of the screaming crowd. The race began with the “mossa” (movement) in Piazza del Popolo and ended in Piazza San Marco, now Piazza Venezia, with the “ripresa” (recapture).

The last day of Carnival, celebrated with the “moccoletti”, brought together in one great event all of the themes of the festival: the calling of the dead, the nullifying of differences of class, sex or generation, the ritualisation of violence, the purification of evil and, especially, an extraordinary beat of collective liberty. Each person strove to keep alight their “moccolo”, the candle which they held in their hand, and, meanwhile, to put out the candles of those around them. Whoever, prince or pauper, lost their candle flame became the target of attacks, to which they could not respond.